- Home

- Daniel Parme

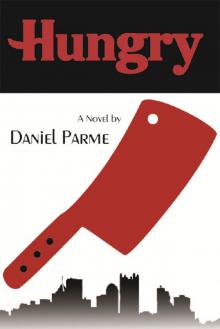

Hungry

Hungry Read online

Hungry

A Novel by

Daniel Parme

Copyright © 2012 by Daniel Parme

Publish Green

212 3rd Ave North, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401

612.455.2293

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

Cover art by Sean O'Donnell

ISBN: 978-1-938297-83-0

Chapter 1

The thing about first ascents in the Yukon Territory is that the Yukon Territory is a fucking long way from Pittsburgh, PA. It’s a journey requiring many stops and an absurd number of changes in mode of transportation: buses, planes, cabs, helicopters. A ferry. For the first time in my life, I rode a ferry.

The thing about first ascents in general is that there’s only one reason to do something so ridiculous as to willingly put yourself hundreds of feet in the air, hanging perilously close to death, nothing more than the tip of your pick piercing the ice and a nylon rope the width of your thumb to keep you from your severely painful doom: simply put, you want to be badass.

Adventure sports are called adventure sports for a reason. If there’s no risk of life and limb, then there is no point. I find it’s near impossible to impress a woman with a badminton racquet in your hand, both feet firmly on the ground.

Yes, it’s all about the badass. Jason, Erica and I could think of no better way to prove ourselves (to whom or what I’m still not certain) than the first ascent of a potentially treacherous ice route thousands of miles from home.

This is back when being badass was important to me, of course. This is back when my story, the story of Travis Sebastian Eliot, was moving along rather swimmingly. This is back when I was waiting tables, taking people’s money with a relentless assault of charm and product knowledge, taking vacations whenever I had the money – long vacations to climb and ride the mountain trails and raft the white waters, to drink the local beer and fuck the local women.

This ice ascending adventure is back when things were simple and life was as easy as all those local broads. I am glad of that time in my life. I fully believe that every man needs, at some point in his life, to know what it feels like to be a bad motherfucker. I’m glad I got to experience it before the time of men fades forever into a fog of femininity…

This trip was when things were simple.

But the story sometimes takes an unexpected turn, I suppose. Sometimes the characters have no choice but to hold on, white-knuckled, and wait to see how they come out of it.

I came out of this shit more badassedly than I could ever have imagined. I mean, being tough is one thing, but you cross a line that most people don’t even know exists when you get into survival cannibalism. There’s a constitution there that doesn’t seem real to people. It doesn’t even seem real to you. Even when you’re in the middle of the very real act of cutting the meat from your dead friends’ bones, taking a nice big bite of that incompetent fucking pilot, it doesn’t seem real to you.

One of the things about being knee deep in such a situation is that you find out what you’re made of. I was, after the plane went down, made of broken bones and lacerations. And I was made of fear and dread and pain. And I was made of torment.

I know that this all sounds a little gothic or melodramatic or whatever, but that’s the way it was. I mean, they were all dead. My friends were dead, and I was starving. And not starving in the way we Americans throw the word around. This wasn’t I haven’t had my 3 PM McDonald’s run yet starving. This was hallucination-inducing emptiness. This was a searing-pain-in-the-innards kind of hunger.

The thing about mountains is they’re supposed to represent a challenge – this enormous mass of earth and rock, put there by whatever god you see fit, is meant to dwarf you. It’s supposed to humble you, remind you that you’re small.

Then again, maybe the mountains don’t represent a damn thing. Maybe they’re nothing more than little fits of rage thrown by our gracious Mother Earth, who doesn’t waste her time with small gestures of displeasure. She has no wooden spoon, no need to bother with time-outs or groundings. These punishments carry no weight in a house with billions of children. Instead, she has shiftings of tectonic plates, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes and tsunamis that swallow entire cities. When that bitch is angry with you, you’re going to know it.

You might not know exactly why you deserve this punishment, but hell, sometimes it’s better not to know how much of asshole you really are.

Of course, I can’t say that Mama threw her best at me. All I had to deal with was the cold, really. And the quiet.

At least, those were the only factors she’d thrown into the equation. She certainly had nothing to do with all the months of planning, saving money, packing all that sub-zero sleeping gear and ropes and spikes. She had nothing to do with our decision to find the cheapest air-fare possible, no matter if the plane looked more like a Volkswagen than a flying craft of obvious genius, no matter if the pilot seemed a little, well, iffy. No, these were all decisions made by three reasonably bright people. Three good friends who just wanted a grand adventure and their names attached to something awesome.

This was the kind of shit that left me thinking I’d be spending the rest of my life with the arctic night sky as my only scenery, the stars and constellations the only names I’d have to call to. When you get to thinking that you’re going to die a slow, painful, lonely death, you begin to see how ancient peoples could have thought the stars were listening to them. Those stars, they’re always there. Every night, looking in on you. Why not talk to them? You’ve got all the time in the world before anyone will rescue you. Or before you die.

Chapter 2

In the months after they found me, it was mostly questions. People want to know, I guess. They did, after all, discover me unconscious and buried beneath layers of jackets and sleeping bags. They found me with ice in my beard, blood-soaked clothes, and blood-stained cheeks. They found what was left of a shitty little plane buried in the snow that had been drifting for a hundred-and-twenty-four fucking days. They found the faces of my friends.

So they had a lot of questions. Of course they did.

And this wasn’t even the shrinks. Not yet. This was the orderlies. This was the nurses, nurses’ aides, nursing students asking me all these questions. They’d be feeding me – it was months of well-rounded meals of chicken and peas and rice and tall glasses of juice and milk – when one of them would say, “What was it like? I mean, eating your friends? How did you do it? It’s amazing.”

Or they’d be bathing me. It was months of sponges and averted eyes; of young and beautiful women in scrubs who made you think maybe you were in a porn, only no one told you. Or it was some middle-aged guy who tried to talk about sports or the news or something, anything to keep his mind off the fact that he was giving a sponge bath to another man. They’d be bathing me, and they’d ask, “How did you get through that? I mean, over four months? Where did you find the strength? I’d have just died. It’s totally amazing.”

They had a lot of questions, but I wouldn’t answer them. I was tired. I was emaciated and tired. I was broken. They’d even had to re-break and reset some of me – the parts of me that had already begun to heal without proper medical treatment. In a lot of places, I was broken. Both legs (in different places), a few ribs, one wrist and forearm. They told me I was lucky to have sustained only these injuries. Apparently, people know nothing of luck.

Still, again and again they asked, and again and again I avoided giving an answer. I just couldn’t.

Even if I could have, wh

at would I have said? It was amazing that I was still alive. Any idiot could have told you that. Plus, I knew there would be plenty to talk about with the shrinks.

“How did it make you feel, seeing everyone dead? Realizing you were lost? Realizing you had no food? Deciding that it would be better to eat your friends than to die there, alone on that mountainside? How did you feel when you finally cut into the rear end of the pilot? Chewed his fat, his muscle, his skin? Swallowed it? And the rest of him? Was he easiest because you didn’t know him? And your friends; was it more difficult for you to eat them? Or did it just not matter anymore? How do you feel about it now that it’s all over?”

These, of course, were only a few of the questions. People want to know. Those doctors, they want to know everything.

But these were my answers: Shocked. Lost. Hungry. Traitorous. Sick to the pit of my soul’s stomach. Sick to the pit of my own stomach. A little numb. Full. Of course the pilot was the easiest. Harder for the friends. Of course it mattered. I feel like I got shafted by some invisible force that either forgot about me entirely or wanted to see what would happen if I were forced to decide between cannibalism and death, and that I must have put on a goddam good show, seeing as you assholes want to know so much about it now.

By the end of it, they said they were glad I stopped talking to the stars, lest I developed some sort of split- or multiple-personality disorder. That didn’t really make much sense to me, but then, I’m no professional. They also said that I seemed to be a reasonably emotionally stable young man, and that I seemed to be dealing with the unfortunate circumstances leading to the cannibalization of my friends about as well as could have been hoped for. By the end of it, they said I was well enough to go home. They said they thought it would be best for me to continue talking to someone, because you never know what sort of residual affects an event such as mine might have on one’s psyche. They said that, soon enough, my memories of the accident would settle down into the muck that is the rest of my brain. It would sink in, and I’d have to get my hands dirty if I ever wanted to really get a good look at it again.

After an unfairly long six months, they said I could go home.

I said thank fucking god and good riddance.

And I went home.

Chapter 3

As it turns out, while I was in the hospital recovering for all that time, my little story had become something of a national phenomenon. It was all over the local news channels at first, giving all those stories about electrical fires and potholes a well-deserved break. From there, it picked up steam and made it to the biggies: CNN, CNBC, FOX News. People all over the place had heard about this guy whose plane went down in the mountains, and everyone else died, and he had to eat them so he wouldn’t die.

It was amazing. It was “the most harrowing tale of survival of the decade.” It was “this decade’s Alive.” It was all a little ludicrous, if you ask me.

But American society is absolutely fascinated by harrowing tales of survival, so I got to be famous. People want to know. They want to know so they can forget about their own lives for a little while. Or they want to know so their lives don’t seem all that bad.

Either way, I was everywhere. Apparently these kinds of things make for good television. The more outlandish, more gruesome, and more humorous, the more air time, more air time, more air time.

And, as surprising as this may sound, it was relatively easy to make light of the whole situation. I got a good laugh about “chewing the fat with my buddies” while I was stuck up there. And I had a bit about pulling the pilot’s leg – it had been severed, you see, and I’d found it about fifty yards from the plane. Both anecdotes were well-received on Letterman, and then again on Leno. Unfortunately, Jay’s first guest was Penelope Cruz, and she seemed none-too-thrilled with all the gory details. In fact, after the show, she took off before I even had the chance to ask for an autograph.

I did get one hell of a nice gift basket for doing the show, though. Expensive shampoos, conditioners, soaps, lotions. There was a mug and a hat. There was a box of the best chocolate I’d ever eaten (dark, smooth, and sexy – the way I imagine Billie Holiday). And there was a slew of other shit I’d never use, but which all seemed pretty pricy.

I gave most of it to the girl who had been taking care of me during my visit to the studio. She was this tiny bit of a thing with dark, dark hair, dark, dark eyes, and toothpaste commercial clean teeth. And, hidden somewhere inside of her, a nuclear power plant produced more energy than her little body could have used in a century.

“I met that guy who cut off his own hand when he was here last year,” she told me after the show. “Did you hear about him? He got his hand crushed by this huge boulder and he was stuck there, for like, days, and he was out of food and water, so he just took out his pocketknife and started sawing away. God! I couldn’t imagine, could you? He was sort of nice. Smiled a lot and said ‘thank you’ when I brought him a soda.” Think about one of those rubber bouncy balls you get from a gumball machine in Wal-Mart, and then imagine throwing it off the wall inside a closed phone booth. That’s what it was like listening to her talk, watching her run around the room doing whatever it was her job required of her.

“And I saw you on Letterman the other day,” she said. “It was funny. Don’t tell anyone, but,” she threw a glance at the open door, “I think he’s funnier than Jay.” As soon as she said it, the little walkie-talkie clipped to her belt said something to her I couldn’t understand. She unclipped it from her belt, turned away from me, and said something back.

“Maybe you shouldn’t have said that,” I told her.

“No. That had nothing to do with Jay not being funny. Brad Pitt’s coming in tomorrow, so there’s a lot of work to do. That was just my boss reminding me to get the pomegranates.” She was totally serious.

“Pomegranates? Really?”

“Yeah, really.” She said it like she couldn’t believe I was surprised. “He also likes to drink this really expensive wine. We order it from Pennsylvania, of all places. I have to make sure to get everything before I go home tonight. No time tomorrow.”

“So Brad Pitt’s sort of a diva, eh?”

“Not really. He’s actually really nice. We just try to take extra good care of all the really big guests that come on the show. That’s all.”

I couldn’t help myself. “So where’s my exotic fruit and expensive wine?”

She snatched a clipboard off the table and held it to her chest. “Oh. Well, you’re not really a star, so you only get a basket. My boss says that fifteen minutes only gets you a month’s worth of personal hygiene products. For some reason, he thinks it’s funny.”

“Yeah,” I said. “That’s not funny at all. Still, it is a pretty nice basket.”

“It is.” She made a quick survey of the room, but I guess she decided she had nothing else to take care of. “Well, I have to go. It was nice to meet you, and thanks for the shampoo and everything. Someone will be here in a minute to see you out. Good luck.” And it was like she vanished, poof, into the air that would tomorrow find its way into the lungs of the sexiest man alive.

This was to be my fifteen minutes. Talk shows (late night, prime time, daytime), newspaper articles, magazine interviews. People shaking my hand on the street. It was a wild ride, this fifteen minutes, but it didn’t really get me anywhere. All I had to show for my fame was a stack of periodicals, a lifetime supply of shampoos and conditioners, and quite a collection of knick-knacks, trinkets, from NBC, CBS, ABC, FOX. You know: hats, mugs, magnets. That kind of shit.

Other people get these things while on vacation in Atlantic City. Other people get these things as souvenirs. I got these things as payment, which would’ve been great, if I could have used them as legal tender. But no matter how hard you try, you’ll never convince the student loan people that this ball cap signed by Larry King is worth this month’s payment. They’ll just laugh at you.

They’ll laugh at you,

but won’t accept your payment, which means you have to try to find some way to make money.

I went to publishers. I was sure that I could have written a book, and it would have sold. I did, after all, have my Bachelors in Creative Writing, and if people are going to read Liza Minnelli’s autobiography, they’ll definitely read about my ordeal. But the book people, they said no. Corporate bastards. “It’s been done,” they’d say. “Once you’ve read one book about survival cannibalism, you’ve read them all.”

Goddam rugby teams in the Andes. Goddam Donner Party.

So no book deal for me. I’d have to find a job. I’d have to go back to the way life was before all the pain and death and fame and parties. But not right away. I always made sure to have a small savings before I went on a potentially hazardous trip, you know, just in case.

I could just go home.

It was an exciting prospect.

Chapter 4

All my life, except those four years at college in Johnstown, home was Pittsburgh. Biggest small town in the country. Steeler Country. Black and gold banners hanging from the telephone poles. Vendors on street corners, peddling bright-ass yellow shirts that said things like “Cleveland Sucks” and “If You Ain’t a Steeler Fan, You Ain’t Shit”. Pierogies, Primanti's sandwiches, and bottles of Iron City. This was home, and it was the first I’d been back since I tried to go climbing with my friends.

“How was your vacation?” Mr. Hanlon, the landlord, gestured me inside his apartment. “Looks like you lost some weight, kid.”

“Yeah, a little.” I avoided the question about my vacation.

“Well,” he said, “people missed you while you were gone.” He crossed the room to a stack of boxes, rested his eighty-six-year-old elbow on top. “I’d love to carry them up for you, but I might die.”

I laughed. I was allowed to laugh. Mr. Hanlon was perhaps the coolest old guy I’ve ever known. He’d been a steel worker before WWII, where he suffered some sort of injury. When he got home, he found out his wife had been having an affair with their dentist. “I always knew she’d do something like that,” he’d said. He didn’t even seem bitter about it.

Hungry

Hungry